I recently read an essay where the author, inspired by yet another writer of essays, shared a few pieces of their “personal lore.” I find this compelling as it encourages the writer to share the backstory for why they are the way they are. A fun thing about it, too, is the very nature of personal lore: factually based, yet not always dependent on verifiable facts1. This allows the teller to focus more on the important part of the tale, be it the moral lesson or the punchline, and not get tangled in the minutiae of unnecessary details.

I figured this was a good platform to occasionally share some of my own personal lore as it relates to the societal topics Iconoclast aims to cover and (often) dismantle. Maybe it’ll be a series?

ON BODY IMAGE

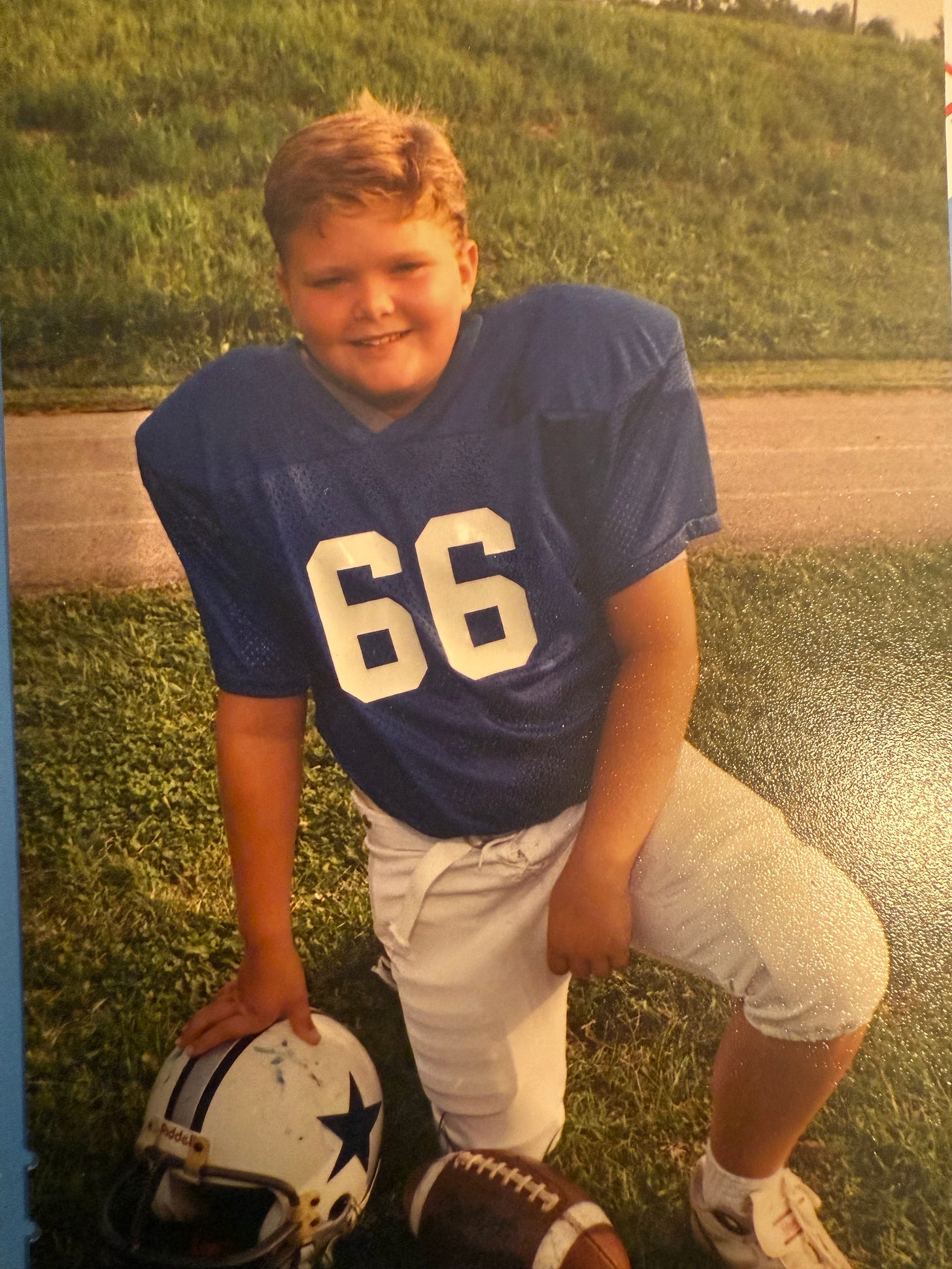

I played pee-wee football in 4th and 5th grade thanks largely to a push from my step-dad and some admitted FOMO I had picked up after my biological dad’s step-son2 started playing. When I signed up, I didn’t know much about the sport but was hyped to be drafted to play for the Cowboys since this was during the legendary Troy Aikman / Emmitt Smith era in the NFL. I took my blue jersey home with pride despite not knowing much about how to actually play.

I didn’t have as much to learn as the other boys however. I was an overweight child and our local pee-wee league had certain weight limits. If you were over a certain weight, you could only play on the offensive line. Exceeding a second, higher weight limit would render you ineligible to play. I was over the defense weight limit my first year, but under the league’s limit, so I accepted my future as an offensive right guard (sometimes right tackle).

I can’t say that I was struggling with my weight during this phase of my life because it wasn’t affecting me in any real way other than being a verbal punching bag for bullies at school. Either way, I certainly wasn’t doing anything to reverse it. I was just being a kid and my (at the time) picky-eater palate only tolerated a small selection of junk food. I was overweight but happy and otherwise healthy.

A few weeks before my second season, I was over the eligibility weight limit by just a couple of pounds. My family put me on a diet that consisted primarily of vegetables and I hated it. We’d go to our local Piccadilly restaurant and get vegetable plates and I felt like I was being tortured. Additionally, my Paps passed me a couple of fluid pills to get me to flush out whatever water I was retaining in the days leading up to the league’s official weigh-in. I made weight that year, but just barely.

This led to what is still one of the most humiliating moments of my entire life. My just-barely weight had gotten the attention of the league and I had been flagged for a mid-season weigh-in. Just before a game, my coaches called me into the small fieldhouse and I joined them inside. They closed the door to what was now a dark room, lit only by a single incandescent light bulb that was hanging from a wire. About eight adult men stood around me in a circle. I was told to strip down to my underwear and step on a scale that had been situated in the center of the room near where I stood. I was fat, already self-conscious about my body and now I was being publicly weighed while wearing tighty whities.

I remember the coach pushing the poise weight along the beam as I stood there, hoping nobody could see my belly hanging over the elastic band of my underwear. I made weight by only about a pound and would be allowed to play that day. When I stepped off the scale, the men (nearly all of whom were overweight themselves) began body shaming me and making snide comments about how chubby I was, throwing around words like “husky” and “stout” (one even poked me in the boob) before filing out of the room. I gathered my clothes and what was left of my 10-year-old dignity, praying that the daylight that was now streaming in through the doorway didn’t illuminate my nakedness for my teammates to see outside.

This moment, paired with the pre-season dieting did little for my confidence and self-esteem. In fact, I think it made it much worse. I would continue being overweight to some degree and was frequently bullied for it. Thankfully, puberty swooped in shortly after that fateful afternoon in the fieldhouse. I shot up to six-feet tall in the next couple of years, making me carry my weight differently. I stayed active playing football, basketball and throwing both shot put and discus in track. Still, I remained overweight and under-motivated until my late 20s.

Much of my weight loss in my 30s was motivated by potential health issues had I not taken action, but that day in the fieldhouse has always been in the back of my mind. I’ve now grown to be an obsessively fit 40-year-old man who has body image issues that remain tied to that traumatic event. No matter how much weight I lose, or how juicy my muscles get or how shredded I look in the mirror, I only notice the imperfections. Some would say it’s body dysmorphia but I’ve never been diagnosed (and don’t care to pursue it). All I know is when I see those old stretch marks that have been on my stomach for over 25 years or I see photos of my belly sticking out in an ill-fitting t-shirt, it brings back memories of that musty fieldhouse where I was treated like back-of-the-pack prey, surrounded by predators.

Every rep I complete in the weight room and every step I take on the running trail is me saying “never again.”

ON RACISM

I attended a pre-K program at a daycare in Allandale called Pow Wow. For that to have been so long ago and for me to have been so young, I’ve maintained quite a few memories. There was my first “girlfriend,” Ashley, who broke up with me for a first grader when we started kindergarten, and my best friend Phillip who had bright red hair and posed his Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles action figures a certain way when we were done playing with them. We had that one new girl who played McDonald’s with us on the playground but didn’t know you weren’t supposed to actually eat the wood chips we used as Big Macs and ended up throwing up sawdust. I once swallowed a Chuck E. Cheese token and proceeded to choke on it before politely asking – while gasping for air – if I could use the restroom so I could choke it up, and the time I accidentally scratched long abrasions on my face while we watched a VHS copy of Little Lulu cartoons from the 1940s.

One of the things I remember most, however, was the time I broke a kid’s ink pen. I was really young (four or five), so I’m not sure I was even aware that there were people in the world who had a skin color different from mine. Having lived (actually been alive) in small-town Tennessee for less than a handful of years, I had never encountered anyone of a different race in person. That all changed when my class at Pow Wow got its first Black kid. I don’t remember his name, but I do remember his warm brown skin and his dark black hair.

We hit it off almost immediately. I showed him where all the toys were and invited him to play some of the group games we hosted outside (I’m sure I also told him to not eat the wood chips). From what I remember, he was pretty cool and I felt proud that I had made a new friend.

I remember climbing up into the car when my grandparents came to pick me up one afternoon. They didn’t know I was friends with this kid, but they saw him and chose to use crude language when describing him. At that age, I didn’t know what racism was so I certainly didn’t understand the words they were using were inappropriate. I did, however, think they sounded funny, so I started using them in the backseat, laughing between parroting the derogatory terms. After a moment or two of this behavior, I was reprimanded for using the words, being told I shouldn’t use them because they’re “not nice.” I wondered why my family would openly use the words if they weren’t nice? How were they going to say them, then tell me it wasn’t right to say them? And why were they using “not-nice” words to refer to my friend?

Because he was “different.”

This subconsciously crept into my young mind and it changed the way I behaved. I began bullying him in little ways throughout the day and felt authorized to do so because, as my grandparents said, he was “different” from me. They spoke of such things as though it was an abomination to be different and not something to be celebrated, and my impressionable mind conformed in turn. It culminated in me asking to see an ink pen he was holding, only for me to turn it sideways against my shoe and break it half. I’d seen some of the older kids break pencils with their hands and I wanted to try it. I didn’t want to use my own pencils so I chose the “different” kid’s pen.

He scrambled to grab up both sides of the broken pen and held them together almost like someone who had discovered a lifeless pet on their back porch. His eyes welled up with tears as he said, “That was my mom’s pen,” before breaking into a loud sob. In that moment, the hateful, hurtful words and opinions of my grandparents meant nothing. I didn’t care what they had to say about my friend, I now knew all I needed to know about him. He was a kid just like me, who loved his mom just like me, who was sensitive just like me.

The only difference is he wasn’t a pompous, entitled asshole kid like me. He was a human — my friend, no less — and nothing else mattered.

I apologized for what I’d done and gave him a hug. I also vowed from that moment on that no matter what my family said, I would never allow myself to feel superior to anyone on such a shallow, hate-filled basis. It allowed me to grow into an adult who, despite living in the American south, does not — and will never — sit idly by while others say racist shit.

-jtf

I am talking about personal lore, not cable television news, believe it or not.

Call me petty, but I refuse to refer to him as my step-brother.

I want to take a sledgehammer to the junk of each and every one of those men. Just saying.